Animation has long been a medium for exploring complex ideas about humanity and technology. Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995), a landmark Japanese animated film, exemplifies this by blending cyberpunk aesthetics with philosophical questions about identity and reality. This essay will analyse how the film reflects animation’s ability to visualise abstract concepts through its portrayal of cyborgs, urban spaces, and existential crises.

Oshii’s adaptation of Masamune Shirow’s manga reimagines the cyberpunk genre by grounding it in a hybrid cityscape inspired by Hong Kong. As Wong (2000) argues, colonial cities like Hong Kong are best suited to create urban landscapes that embrace racial and cultural diversity. The towering skyscrapers alongside traditional Tong Lau buildings , symbolizes the clash between modernity and tradition in postcolonial era. This hybrid urban space, where overload information conveyed in neon billboards, giant screens and monitors compete with concrete reality, mirrors post-human’s existential crisis. Norman McLaren’s definition of animation as “not the art of drawings that move, but the art of movements that are drawn” (McLaren 1949) finds radical expression here: the city’s flickering holograms and hand-drawn motion of electronic and mechanic components are used to destroy perceived reality.

The film’s exploration of identity reflects broader theories of posthumanism. Cyborgs in Ghost in the Shell challenge traditional definitions of humanity, as biological and mechanical elements merge. Motoko’s existential crisis—questioning whether her memories or “ghost” (soul) define her—echoes debates about consciousness in an age of artificial intelligence. As Hayles (1999) notes, posthumanism redefines the self as “an amalgam of biological and informational patterns,” a concept visualized through Motoko’s mechanical body and digitized memories. The film’s climax, where her consciousness merges with an AI program, further destabilizes the boundaries between human and machine.

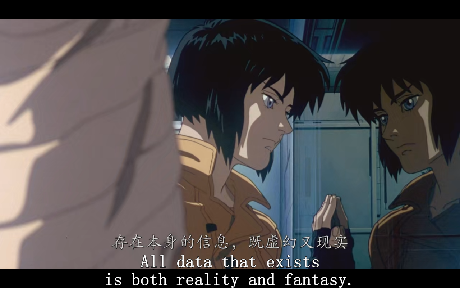

Animation techniques also amplify the film’s themes. Oshii employs reflective surfaces and fragmented screens to create visual uncertainty. For instance, windows and mirrors often distort reality and symbolize the blurred perception of the characters. These images are consistent with Bukatman’s (1993) assertion that cyberpunk animation “disrupts spatial logic to mirror psychological disorientation.” Oshii puts emotion over action and tells the story at a slow pace, inviting the audience to question the nature of existence – a goal that can be achieved through animation’s unique ability to manipulate time and form.

In conclusion, Ghost in the Shell proves that animation can use visual language to address the most complex philosophical questions. This film invites us to reflect on the nature of reality and our place within it, urging us to consider the implications of living in a world where the boundaries between human and machine are increasingly blurred. This is not only a masterpiece in the history of animation, but also a new direction for science fiction.

References

Bukatman, S 1993, Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction, Duke University Press, Durham.

Hayles, N.K 1999, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Wong, K 2000, ‘On the Edge of Spaces: “Blade Runner”, “Ghost in the Shell”, and Hong Kong’s Cityscape’, On Global Science Fiction, vol.27, no. 1, pp. 1-21. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4240846.

Leave a Reply